Why corporate climate action needs more than just emissions targets

We dive into the NewClimate Institute’s latest report on corporate climate action. We take a look at the central finding - that emission reduction targets alone are failing to deliver climate action - and its proposal for transition-specific alignment targets as a solution.

Halfway through a crucial decade

We are halfway through a decade in which global emissions need to fall by half (relative to 2019) to keep global warming below 1.5C. And things are not going to plan.

The latest scientific research suggests we have already temporarily broken the 1.5C threshold (though this is typically measured over decades). At the current pace of annual emissions, the remaining carbon budget for 1.5C could be used up in about three years.

With some estimates suggesting that global warming is currently on track to reach around 2.7C, every tenth of a degree of additional warming that can be avoided makes a difference.

Corporate climate progress - a murky picture

The NewClimate Institute’s Corporate Climate Responsibility Monitor provides a rigorous and clear-eyed assessment of how companies are contributing to the climate transition. The report evaluates the transparency and integrity of leading companies’ climate pledges, identifying examples of good practice and opportunities to enhance corporate climate governance.

To date, governance has primarily focused on encouraging companies to set and deliver on emissions reduction targets as a way of aligning corporate climate action with global efforts to reduce emissions in line with 1.5C.

But, in its latest report, the NewClimate Institute questions whether emissions reduction targets by themselves are fit for purpose for achieving this transition. The report notes that:

- It is becoming increasingly difficult to understand the level of ambition companies are committing to achieve by 2030;

- Emissions reduction targets generally do not seem to be translating into meaningful changes in companies’ business models that address their most critical emissions sources;

- This is particularly the case for companies in sectors with large scope 3 emissions.

Structural issues in corporate footprints

To be clear, the report isn’t apportioning all the blame to companies. NewClimate Institute notes that firms increasingly understand what constitutes credible corporate climate action. And there are many examples of firms who are making meaningful progress on their emissions targets.

Instead, the report raises questions about the effectiveness of emissions targets as the sole governance mechanism for delivering climate action. Highlighting how structural issues in emissions footprints and targets - and the way they’re reported - are making it harder to understand actual commitment and progress.

Disclosure gaps between companies’ emissions footprints make it difficult to track emissions trends over time, interpret targets against base years, and compare ambition.

This is a particular issue for scope 3 - which, as we discussed in detail in our November newsletter, presents a number of challenges including being tricky and imprecise to measure, hard to interpret, loosely defined under current target-setting approaches, difficult to influence, and hard to track.

The NewClimate Institute also highlights certain problematic carbon accounting practices that have become prevalent in different sectors.

For example, firms in the tech sector take very different approaches to acquiring renewable energy and reducing their market-based scope 2 emissions - from high-quality constructs such as onsite renewables and PPAs to lower-quality interventions such as buying unbundled RECs. Meanwhile, the report notes that automotive manufacturers may be guilty of underreporting emissions, especially when estimating vehicle use-phase emissions.

Transition-specific alignment targets as a way forward

To address these issues, the NewClimate Institute suggests that companies be required to complement their emissions-reductions targets with transition-specific alignment targets.

Put simply, these targets are:

“metrics that directly measure a company’s progress on key climate change mitigation transitions, tailored to their specific sectors and business activities”

(NewClimate Institute)

Such targets put the focus on near-term actions and sector-specific transitions that relate to key emissions sources associated with firms’ main business activities. And would complement existing emissions reduction targets.

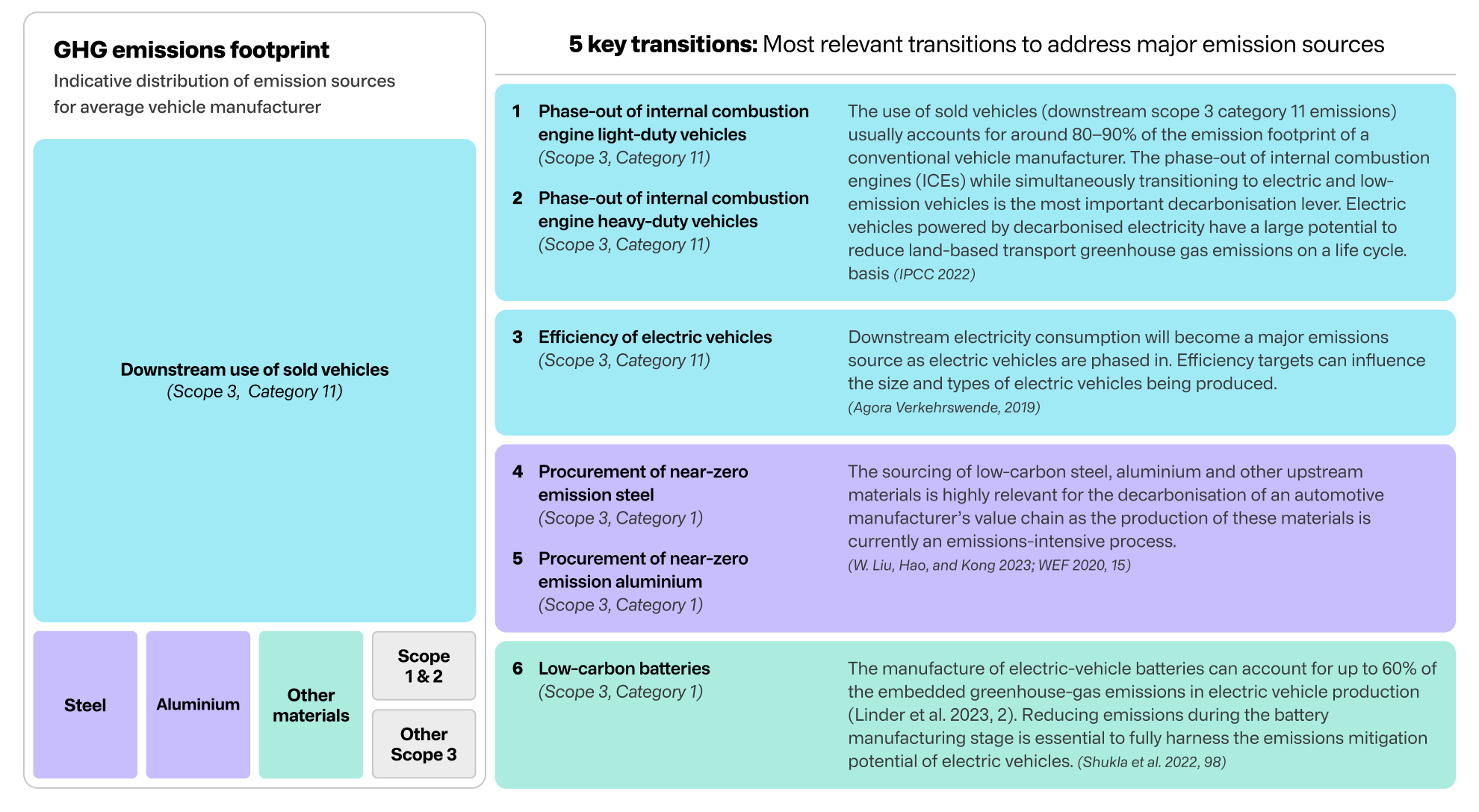

Examples could include targets for the percentage of annual sales of battery electric vehicles for automakers, or zero deforestation targets for agri-food companies, or targets for the share of hourly matched electricity from owned or third-party data centres for tech firms.

Setting targets based on clear outcome measures that reflect expected decarbonisation transitions should act as leading indicators - showing whether companies are on track for long-term emissions reductions by focusing on near-term, high-impact actions.

This idea is gaining some traction. The Science Based Target initiative (SBTi) is considering a version of this approach as part of updates to the Corporate Net Zero Standard. In its draft consultation, the SBTi proposes that companies publicly report more granular GHG inventories, including at the activity level for all emission-intensive activities.

The SBTi is also considering whether companies’ emissions reductions targets should be disaggregated into separate targets for the most emissions-intensive activities. For now, the draft version of the standard falls short of requiring companies to set associated transition-specific alignment targets as proposed by the NewClimate Institute.

One challenge is that defining transition-specific targets will be easier for some sectors than others. It works best where business activities and emissions sources are relatively similar, emissions are concentrated, and there is broad consensus on decarbonisation pathways.

The NewClimate Institute identifies four sectors (automotive, tech, fashion and agri-food) that could be well suited to this approach. A small number of transition-specific indicators could cover a large share of total emissions for these industries. By contrast, it may be less appropriate for other sectors, such as chemicals or consumer goods.

The Minimum Line

The NewClimate Institute puts its finger on a growing tension in corporate climate action: target-setting is accelerating (by the latest count some 11,200 companies have committed to setting science-based targets), but the real impact remains murky.

Transition-specific targets offer a clearer lens - directing companies towards the most emissions-intensive parts of their footprint and identifying the key actions that can actually move the dial. For many sectors, the prescription for decarbonising will be similar, and progress on these actions can meaningfully complement emissions reporting.

But to get there, companies need carbon footprints that are sufficiently granular - detailed enough to move beyond high-level categories and pinpoint the specific activities driving emissions.